.

The following article appeared on October 7th in a number of Catholic publications. I find it interesting that there have been quite a few lectures, speeches and articles making this same point recently, all by prominent individuals. What exactly might be the reason for wanting to make the point that Chant is the ideal of Catholic liturgical music and should serve as the model in any renewal of Sacred music?

>>>>

Chant Will Renew Sacred Music, Says Vatican Aide

-Notes Its Link to Liturgical Texts

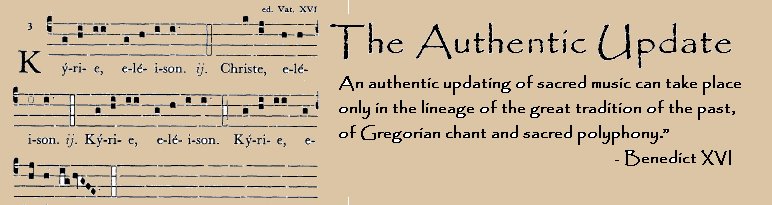

ROME, OCT. 7, 2010 (Zenit.org).- Sacred music cannot be limited to Gregorian chant, but it is chant that contains the key to renew liturgical song, according to a consultor for the Office of Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff.

Father Uwe Michael Lang, also an official of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Sacraments, made this observation Wednesday at a lecture at l'Accademia Urbana delle Arti in Rome.

Father Lang pointed to the 1749 encyclical "Annus Qui" by Pope Benedict XIV as the "most important papal pronouncement on sacred music" prior to Pope St. Pius X's "Tra Le Sollecitudini."

The 18th century encyclical "proposes the important criteria of sacred music that are valid beyond the limits of their historical context and resound also in our time," the priest said.

Father Lang explained that the encyclical presents plainsong as normative for the Roman liturgy "while it approves unaccompanied polyphony and also permits orchestral music, though with certain conditions, in divine worship."

He said this position of the Church is reflected in the constitution of sacred liturgy from the Second Vatican Council, which "exalts Gregorian chant as the 'proper' music of the Roman liturgy."

"The pre-eminence of chant," Father Lang further recalled, "was confirmed by Benedict XVI in his 2007 post-synodal apostolic exhortation 'Sacramentum Caritatis.'"

Father Lang proposed that the value of Gregorian chant is "its profound relationship with the liturgical text, to which it gives musical form."

"'Annus Qui' requests explicitly the integrity and intelligibility of the texts that are sung in the Mass and in the Divine Office," the priest affirmed. "This concern was already debated in Trent, but not included in the council's official documents."

He added that though "sacred music cannot be limited exclusively to Gregorian chant, it has in itself, however, the keys for a true renewal of sacred music."

>>>>

And so, as is pointed out by Fr. Lang, Gregorian chant has always been the ideal form of Catholic liturgical music, and that position was strongly reinforced by the Second Vatican Council and has been re-iterated by all Popes since that time and there has been no document or proclamation to the contrary. But we all know what the status quo is, so why come out and say this again at this time? And why go as far back as “Annus Qui”… a prominent document from a previous Pope Benedict?

And why make the point that Annus Qui proposes the important criteria of sacred music that are valid beyond the limits of their historical context and resound also in our time. Note that he doesn’t say that “Annus Qui” proposed these criteria… he says that the document proposes these criteria. This may be nitpicking to an extent, but I think there is a difference in point of view when one speaks about documents of the Church. When one generally sees older documents as outdated and irrelevant, those documents claimed… or stated… or proposed specific ideas that are no longer relevant. They are past tense… no longer valid. But when one accepts the validity of a past document as relevant in our own day, that documents claims… or states… or proposes its ideas to us still, and they are as relevant now as in the past.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t documents and teachings of the church that are no longer valid, but when that is the case, those documents or teachings are abrogated, such as Ecclesia Dei Afflicta was abrogated by Summorum Pontificum. That abrogation is noted in the new document and it is specifically spelled out that the provisions of the former document are no longer in force. But in the case of Annus Qui, it’s provisions have been re-iterated and strengthened, first by Pope Pius X in Tra le sollecitudini, and then again more comprehensively and forcefully through the documents of the Second Vatican Council, again in 2000 by Pope John Paul in his Chirograph on Sacred Music, and most recently by Pope Benedict in Sacramentum Caritatis. Rather than being abrogated, it is clear that the criteria and concerns so eloquently and clearly laid out in Annus Qui have been re-iterated and reinforced from the 18th century up to the present day without exception.

And what are those criteria and concerns laid out in Annus Qui? What were the reasons given for the reform of Sacred Music by Pope Benedict XIV?

•Sacred Music must be distinct from popular (theatrical or profane) music.

•Instrumental music poses the danger of profanation by association with popular or theatrical music. Recent practice and some local customs which encourage the use of popular instruments and singing styles within the Church are to be eliminated.

•When instruments oppress and bury the voices of the choir, and obscure the meaning of words, then the use of the instruments does not achieve the desired purpose, they becomes useless and indeed remain forbidden and prohibited.

•Sacred Music is first and foremost a proclamation of text, and all musical settings must derive from the text and not vice-versa as is the case in popular or theatre music.

•The liturgy must be primarily sung… particularly the words of the prophets, the apostles, or Epistle, of the Creed, the Preface or action of thanksgiving and prayer of the Lord. Practices or teachings that seek to reduce the singing of these parts of the Mass are to be eliminated.

•The distinction between the musical forms of the Office and the musical forms of the Mass are to be observed in recognition of the distinction between the prayer of the office and the Sacrifice of the Mass. To one belongs hymnody and strophic singing, to the other belongs the riches of the chant and polyphony. In both, the texts must be clearly proclaimed and not obscured by the musical forms or instruments.

•The incorporation of popular singing styles and theatrical forms excites the listener and distracts from the sacredness of the Mass, leading the minds of the listener away from the mystery to a place where it remains in the common world.

Other than the occasional references to “bawdy” music and a strong underlying assumption in this document that the reader is familiar with liturgical practices from the time of Charlemagne onwards, this could have been written this year by Benedict XVI rather than in 1749 by Benedict XIV! The concerns are very much the same.

And so I ask again… Why the sudden outpouring of references to these former documents and their relevance today by prominent figures from the Church’s hierarchy? I mean… it’s not like we have the same problems...uhhmmm...OK...Maybe we should think about this a bit.

Friday, October 8, 2010

A Lesson Learned

I’d like to pick up where I left off with my last posting and take a look at another aspect of how the New Translation will affect the direction of Catholic liturgical music, perhaps for many years to come. I noted in my last post how there exists a sort of “soft mandate” that publishers include the ICEL-USCCB produced chant settings of the Mass Ordinary in all published worship materials after the implementation of the New Translation in November of 2011. As it is currently understood, other settings will be included, but none have yet received approval, and even once approved, they will have to be included as secondary settings since the ICEL-USCCB chant settings must be the setting presented in the Order of Mass. This alone will have some considerable consequences for how publishers promote and present their own (copyrighted) settings in published resources. But there is also another aspect of the implementation that may have a much more profound impact on liturgical music, which up to now has been dominated by “The Big Three” (OCP, GIA and WLP) publishers. History can be a good teacher in this case.

The past 10 years has seen the rapid decline of print media. Newspapers and magazines have watched their circulations reduced to non-sustainable levels, requiring mergers, buyouts and large scale layoffs in the fortunate situations – bankruptcies and closed doors in the less fortunate, and lots of lamenting and hand-wringing all around. The lamenting and hand-wringing seems disingenuous though, because the cause is clear and well known: The Internet and the diversity of views that it permits. No longer did the consumer of news and information have to accept what was given by the established media. With the internet anyone can be a reporter and compete with the once dominant publishers and their immense distribution networks. The individual who used to type their own “pamphlets” and hand them out on a corner downtown can now hand them out to the entire world, updating them every day, every hour, every minute if necessary! And the consumer who enters a topic in a search engine finds that information right alongside the New York Times or Wall Street Journal. On the internet, everyone is equally accessible and the page of the multi-billion dollar corporation is exactly the same size as the page for the guy blogging from his smart-phone.

Statistics now show that more people receive their news from websites and blogs than from all print media combined. The internet, a medium that was largely amateur driven and populated by a peculiar and specialized group of enthusiasts only 15 years ago has, in the last 5 years, managed to take on and conquer the one-time giants of the media world. And the point that I would make here is this: the media giants saw it coming and their reaction was to protect their turf by attempting to change the already established rules of the internet game to allow them to import the status quo of their dominance into a realm that had already disposed of them and moved on. The result is a sort of “Jurassic Park” of media dinosaurs relegated to an online island far removed from reality, living out their final days fighting and devouring each other while the rest of the world watches with the sense of detached amazement that comes from seeing once-great beings become inconsequential curiosities. Their extinction had already happened and that fate was accomplished even before the first mouse-click by a force far more powerful than the internet. It was the idea that news and information can’t be owned and sold in a world that now sees it as something free. News and information is a part of the culture and belongs to it, not to the New York Times and not to any company, government or person.

It might be obvious by now that I’m inferring an analogy here to the situation developing in Catholic liturgical music. It’s not really a true analogy because while music exists in real time and is experienced as such through performance, it is also like news and information insofar as it has historically been distributed by publishers in the form of print media which is claimed to be the property of the publisher and which is then sold to the consumer. But liturgical music is also like news and information as a sense is rapidly developing that,in whatever form, it belongs to the liturgy and to the faithful, not to this or that publisher.

So this may not be so much an analogy as it is another part of the same phenomenon described above, but one which has lagged behind slightly because of the slow-moving nature of liturgical music media which renews in one year cycles for so-called “disposable” hymnals, and in 5-10 year cycles for hard-cover hymnals. With the implementation of the New Translation, all of it is “up for renewal” at once, allowing an assessment of options that is unprecedented, at least in modern times. And if that’s true, there may be as different a future for liturgical music now as there was for newspapers, magazines and books 10 years ago.

I am going to end here by looking back to the time 10 years ago when the media giants failed to see the writing on the wall. I would suggest that there has been a lot of writing going on these past few years, and the message on the liturgical music wall is pretty clear. Those who understand the message will be poised and ready, but you really have to understand the message first.

The past 10 years has seen the rapid decline of print media. Newspapers and magazines have watched their circulations reduced to non-sustainable levels, requiring mergers, buyouts and large scale layoffs in the fortunate situations – bankruptcies and closed doors in the less fortunate, and lots of lamenting and hand-wringing all around. The lamenting and hand-wringing seems disingenuous though, because the cause is clear and well known: The Internet and the diversity of views that it permits. No longer did the consumer of news and information have to accept what was given by the established media. With the internet anyone can be a reporter and compete with the once dominant publishers and their immense distribution networks. The individual who used to type their own “pamphlets” and hand them out on a corner downtown can now hand them out to the entire world, updating them every day, every hour, every minute if necessary! And the consumer who enters a topic in a search engine finds that information right alongside the New York Times or Wall Street Journal. On the internet, everyone is equally accessible and the page of the multi-billion dollar corporation is exactly the same size as the page for the guy blogging from his smart-phone.

Statistics now show that more people receive their news from websites and blogs than from all print media combined. The internet, a medium that was largely amateur driven and populated by a peculiar and specialized group of enthusiasts only 15 years ago has, in the last 5 years, managed to take on and conquer the one-time giants of the media world. And the point that I would make here is this: the media giants saw it coming and their reaction was to protect their turf by attempting to change the already established rules of the internet game to allow them to import the status quo of their dominance into a realm that had already disposed of them and moved on. The result is a sort of “Jurassic Park” of media dinosaurs relegated to an online island far removed from reality, living out their final days fighting and devouring each other while the rest of the world watches with the sense of detached amazement that comes from seeing once-great beings become inconsequential curiosities. Their extinction had already happened and that fate was accomplished even before the first mouse-click by a force far more powerful than the internet. It was the idea that news and information can’t be owned and sold in a world that now sees it as something free. News and information is a part of the culture and belongs to it, not to the New York Times and not to any company, government or person.

It might be obvious by now that I’m inferring an analogy here to the situation developing in Catholic liturgical music. It’s not really a true analogy because while music exists in real time and is experienced as such through performance, it is also like news and information insofar as it has historically been distributed by publishers in the form of print media which is claimed to be the property of the publisher and which is then sold to the consumer. But liturgical music is also like news and information as a sense is rapidly developing that,in whatever form, it belongs to the liturgy and to the faithful, not to this or that publisher.

So this may not be so much an analogy as it is another part of the same phenomenon described above, but one which has lagged behind slightly because of the slow-moving nature of liturgical music media which renews in one year cycles for so-called “disposable” hymnals, and in 5-10 year cycles for hard-cover hymnals. With the implementation of the New Translation, all of it is “up for renewal” at once, allowing an assessment of options that is unprecedented, at least in modern times. And if that’s true, there may be as different a future for liturgical music now as there was for newspapers, magazines and books 10 years ago.

I am going to end here by looking back to the time 10 years ago when the media giants failed to see the writing on the wall. I would suggest that there has been a lot of writing going on these past few years, and the message on the liturgical music wall is pretty clear. Those who understand the message will be poised and ready, but you really have to understand the message first.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)